Presidential Drinking

Part 2: Madison to Van Buren

The story of Prohibition is very much the story of America’s relationship with alcohol throughout our history. It has shaped our politics, our culture, and our economy. Changing American tastes and values had enormous influence over just how present alcohol, and what types of it, has been in our society. A fascinating gauge of those changing tastes is looking at how our presidents from the Founding Fathers all the way up to the incumbent have interacted, or not interacted, with beer, wine and spirits.

In this series, Presidential Drinking, we’ve dug deep into what place alcohol had in each president’s life from their favorite drinks to whether it contributed to their business practices throughout their lives to whether they… well… imbibed a little too much from time to time.

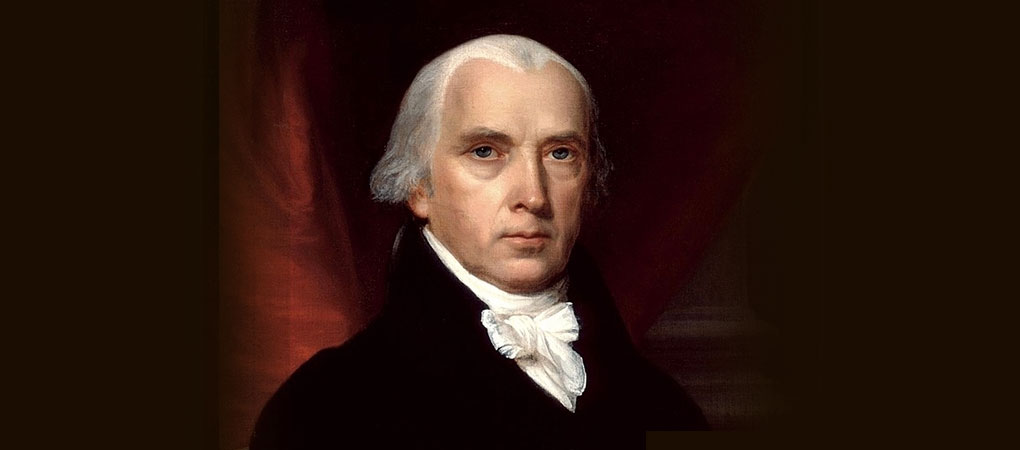

President James Madison, served 1809 – 1817

What was his drink of choice?

Two separate kinds of alcohol come up when reading about James Madison’s drinking habits. The first is whiskey. Reportedly, he drank up to a pint of the stuff every single day. That feels like a lot, until you realize that it’s a volume dwarfed by many of his colleagues and countrymen. With clean water being scarce, it wasn’t rare for men to drink a couple of small bottles of whiskey in a day. Madison was pretty temperate, all things considered! It’s probably for the best. As our shortest president to date, at 5’4”, the stronger liquor might have affected him a little harder than the towering General Washington. His other favorite beverage was slightly weaker and still caused him a bit of pain. He said champagne “was the most delightful wine when drank in moderation, but that more than a few glasses always produced a headache the next day.”

Was he in the booze business?

No. James just didn’t seem enamored enough with the stuff to make it himself. Like many fellow wealthy Virginians, Madison did farm tobacco. However, the early 19th century saw a serious decline in the viability and the profitability of the tobacco crop, and the nation’s fourth president left office less wealthy than he entered it.

Did he party?

Not really. Washington was idolized for his eloquence. Adams was often derided for his arrogance, but celebrated for his intelligence. Jefferson was a snobbish, but social man of many disciplines. James Madison was decidedly an introvert. Supposedly, when Madison lost his hat as a young man, he hid indoors for two days rather than be spotted hatless. As a spirited lover of books, he seems to have much preferred a night in reading as opposed to anything his fellow revolutionaries got themselves into. His bookishness is all for the best.

Madison’s political prowess and intelligence allowed him to become “the Father of the Constitution.” Whatever we feel about his ability to liven up a party, President Madison ended up a dedicated elder statesman and lived to be one of the last surviving men who founded the United States of America, dying at the age of 85 in 1836.

President James Monroe, served 1817 – 1825

What was his drink of choice?

Of his predecessors, President Monroe’s preferences most align with Thomas Jefferson’s. The presidency isn’t the only role the two men shared. Thomas Jefferson was the first person after the American Revolution to serve as Minister to France. That’s what we would call an ambassador today. Later in the Washington administration, Monroe sailed away to France to fill the same role. Unsurprisingly, Monroe developed quite the taste for French red wines and champagnes while serving in the position, just as Jefferson had.

Was he in the booze business?

Many of the lawyers that became president didn’t seem to have much time or will to make their own alcohol. While most of Monroe’s drinking tended to be glasses of wine, he did partake in some fun concoctions!

The Monroe family has their own recipe for a treat called “syllabub.” Basically, you take some cream and whip it together with some sugar and wine. The result is a decadent, airy dessert that was all the rage in Colonial America. Its origins go back even farther than that though. Original recipes date from the late 1400s! Many of the Founding Fathers mentioned enjoying syllabub, but, as far as we’ve seen, the Monroes were the only ones who had their own recipe.

Did he party?

No. Enjoyment of fancy wines hardly lends itself to raucous partying. That doesn’t mean that Monroe’s imbibing had no consequences. At one point during his presidency, 1,200 bottles of French wines were charged to an account meant for furniture purchases. While it was likely an honest mistake, can we really blame President Monroe for choosing alcohol over armchairs? So, while not a party animal, Monroe was drinking A LOT of French wine. Maybe that has something to do with his presidency taking place during the “Era of Good Feelings”!

President John Quincy Adams, served 1825 – 1829

What was his drink of choice?

John Quincy Adams may have inherited his name and his career path from his father, John Adams, but he did not inherit our second president’s obsession with cider. John Quincy Adams was a Madeira man, through and through. While his father drank Madeira before bed, John Q. Adams took Madeira love to a whole new level. Apparently, Adams’ friends had set up a blind taste test for him, and he correctly identified 11 of the 14 Madeiras he sampled. When he was included on historians’ lists of most intelligent presidents, we didn’t think it was because he knew his fortified wines like the back of his hand!

Was he in the booze business?

No. Like the other lawyers before him, President Adams didn’t seem to make money off of the production or sale of liquor. Although, maybe, if he’d avoided the whole presidency thing, John Quincy might’ve made a decent sommelier. Too bad he had to settle for Commander-in-Chief.

Did he party?

John Quincy Adams seems to have taken after his dad’s rival: Thomas Jefferson. Like Jefferson, John Quincy Adams was a big old snob about his drinking. He apparently wrote letters to his mother, Abigail, bragging about a really old wine he’d tried. Still, he didn’t quite reach Jefferson-level snobbery. He once complained about Jefferson’s wine-based yammering after attending one of his dinner parties. John Quincy Adams, like his father, controlled his consumption. The responsible drinking of the Adams father and son may have something to do with another family member. Charles Adams, John Quincy’s younger brother, drank himself to death by the age of 30.

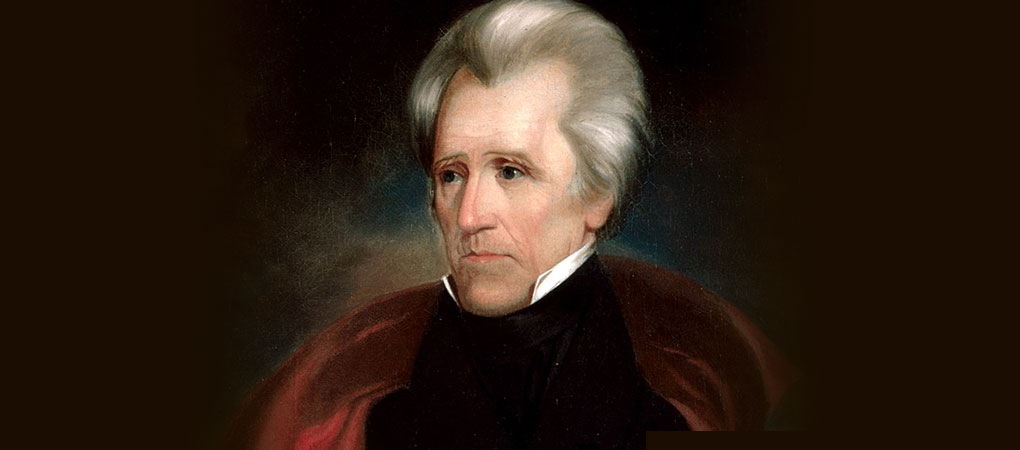

President Andrew Jackson, served 1829 – 1837

What was his drink of choice?

Whiskey all the way. Born in the Carolinas, but a Tennessee man at heart, Andrew Jackson spent all his life drinking whiskey. As you’ll see below, there’s very little of Andrew Jackson’s life that wasn’t soaked in whiskey in some way. Unlike his wine-loving predecessors, he didn’t order from all over the world, but drank where he lived, much of the product being made by Jackson himself. To our knowledge, Jackson didn’t go overboard on his drinking, but his relative sobriety didn’t stop him from becoming one of our most controversial presidents. Today, Jackson is largely remembered for the atrocities of the Trail of Tears, a direct result of Jackson’s policies of forced removal of Native American populations.

Was he in the booze business?

Yes! After a long run of non-distilling lawyer presidents, the election of Andrew Jackson in 1828 fostered in two terms of a distilling lawyer president. At the turn of the 19th century, Jackson owned a distillery. After he moved to his estate, the Hermitage, he opened up a tavern and got into horseracing. Essentially, if he wasn’t doing work in warfare or government, he was probably working on booze.

Did he party?

Absolutely. In fact, Jackson’s propensity for a party is legendary. Other presidents had made sure their inaugurations carried the proper amount of reverence for the office. Not Jackson! He embraced his reputation as a champion of the common man and threw open the doors to the White House. Bowls on bowls of whiskey punch were served. It wasn’t long before the mansion was filled with a drunken crowd, and they promptly wrecked the place!

Later in his presidency, a dairy farmer sent Jackson a 1,400-pound block of cheese which he left in the Entrance Hall of the White House for people to eat. Basically, President Jackson turned the White House into a massive and messy charcuterie board.

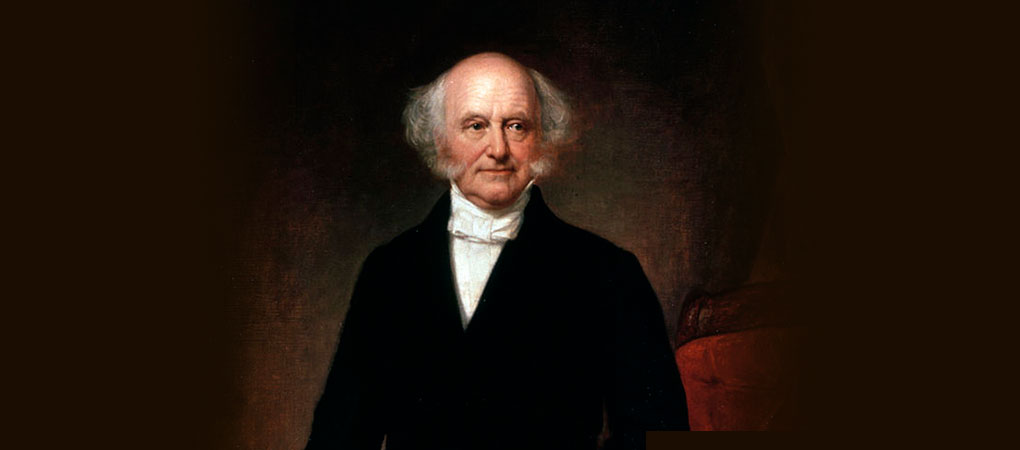

President Martin Van Buren, served 1837 – 1841

What was his drink of choice?

Is all of it a proper answer? No, not really. Even the most prodigious of drinkers have their preferences and, for Van Buren, it was whiskey. We don’t have good records of how much he drank, but we know it was A LOT. Much of what got Martin elected was riding on the coattails of the highly popular (at the time) predecessor that he served as secretary of state and vice president under, Andrew Jackson. He shared Jackson’s politics AND his drinking preferences. After his first term, Jackson replaced his vice president, John C. Calhoun, with Van Buren. While Jackson and Calhoun hated each other by that time (After his presidency, Jackson said, “I regret I was unable to shoot [his political rival] Henry Clay or to hang John C. Calhoun.”) so it’s possible that Jackson selected Martin just to have someone he actually liked to party with at his second inauguration.

Was he in the booze business?

No. It’s possible that he kept a few distilleries IN business, though. As a young adult, he was admitted to the New York bar, but didn’t spend too much time in courtrooms. He got into politics fairly quickly and kept busy as he rose through the ranks of New York and national politics. Plus, his drinking buddy, Andrew, had plenty of liquor for the two of them.

Did he party?

Martin Van Buren went by a few nicknames, most of them bestowed upon him. Old Kinderhook. The Fox. The Little Magician. Van Buren was only 5’6” and folks often attribute small stature to inability to hold your liquor. Nobody challenges that stereotype more than Martin Van Buren. You see, he had another nickname. By 25, he’d become so renowned (or infamous?) for his ability to guzzle glass upon glass of whiskey without appearing any less sober that people started calling him “Blue Whiskey Van.” It was such common knowledge that he drank with wild abandon that his opponents successfully used his habits against him in his 1840 campaign for reelection.

You might know the Panic of 1837 as the economic panic of Van Buren’s first year in office. New York barkeeps know it as that familiar feeling when you’re low on liquor, and Martin Van Buren walks in the front door.