Low Taxes, High Aspirations

“All great and honorable actions are accompanied with great difficulties, and both must be enterprised and overcome with answerable courage.”

– William Bradford, Governor of Plymouth Colony

When some of the first colonies were founded, they were, surprisingly, exempt from nearly all taxes save some import duties and an annual land tax. Administration of the early colonies was mostly done by volunteers and, similarly, things like schools and churches were paid for by volunteer contributions. Over time, these payments would become less and less voluntary by necessity. The generous souls who paid for these societal improvements were recognized publicly with perks like getting the best seats in church. It was a simpler time, but it wasn’t made to last.

By the mid-1600s, there was too much to be done and cared for to continue the tax-free colonies. Infrastructure and buildings needed to be built. Ports and prisons couldn’t be forgotten. Of course, there was also the need to defend against neighboring native tribes and European settlers. The shopping list became much too long for small contributions to suffice. Wealth taxes were implemented based on property assessment as well as poll taxes that gathered money from all men over the age of 16. Although the income tax was still almost three centuries away, a very similar tax on assets and earnings, called a faculty tax, was implemented across New England in that time.

Still, these taxes weren’t exactly egregious impositions. The rates were kept low: only as much as needed to maintain life and growth. Conflicts with native tribes would increase the amounts, but not too much to bear. The commissioner that evaluated asset values was chosen from the town’s population to keep the process fair and democratic. Along with these direct taxes came duties on imported goods such as spices and fruits or on vices like tobacco and liquor.

This is the first appearance in America of what are often referred to as “sin taxes” or “luxury taxes,” indirect taxes placed on items that are deemed not only unessential, but harmful. The benefit, from the point of view of the government, is two-fold: they get to collect revenue while incentivizing the abstention from undesirable behavior. In the Colonies’ fledgling years, the tax was a novelty, a bonus even. However, as the New World grew and a new nation was born, these types of taxes began to take center stage.

The British Are Coming

“The power to tax is the power to destroy.”

– John Marshall, 4th Chief Justice of the United States

Many of the colonies in the New World enjoyed a fair amount of independence from Great Britain’s monarchs. While their charters were granted by the Crown, they were governed by the people who lived there under a charter (charter colonies) or by a “proprietor” (proprietary colonies). At any given time, the charter could be revoked, and the colony would become a royal colony under direct control from the king. As the colonies grew and expanded beyond their capacity to provide for themselves, they were absorbed back into the British Empire and became royal once again.

The conversion from charter colony to royal colony made all the difference as far as taxation was concerned. By the end of the 17th century, the Crown had regained control of the colonies and the days of collecting only the necessary amount of tax were over. The 18th century saw the imposition of all types of much higher taxes and economic monopolies through a whole mess of British Acts: The Molasses Act of 1733, the Sugar Act of 1764, the Stamp Act of 1765, the Townshend Acts of 1767, and the Tea Act of 1773.

While these taxes were endlessly useful for revenue generation and control of trade, the quick succession of excise taxes in the 1760s and 70s spelled the beginning of the end for British rule over America. The Sons of Liberty, a group formed in protest of the Stamp Act, were instrumental in spreading patriotic sentiment across the Colonies. Their motto? “No taxation without representation.” It would be the Sons, headed by Samuel Adams, that would plan and execute a financially devastating protest to the Tea Act: The Boston Tea Party.

In this 1773 Currier & Ives lithograph, the Boston Tea Party is in full swing.

Today, dumping tea into a harbor may seem like a harmless or even silly act of protest, but it’s important to understand just how much damage the Sons of Liberty had done to the British East India Company. When all was said and done, 340 crates (92,000 pounds of tea!) lay at the bottom of the harbor. In modern money, the tea was worth $1.7 million. No person was injured. No ship was damaged. No personal property was destroyed. As a protest against unfair taxation, the message was loud and clear: any act of economic tyranny will be met with economic catastrophe.

It was these dramatic and effective acts of rebellion, all inspired by what the Patriots believed to be tyrannical taxation, that would be the catalyst for the American Revolution. After years of bloody conflict, a new nation rose from the battlefields: The United States of America. While this meant the end for British rule, it was certainly not the end for public outrage over taxation.

The Whiskey Rebellion

“It is with equal pride and satisfaction I add, that as far as my information extends, this insurrection is viewed with universal indignation and abhorrence.”

– George Washington, 1st President of the United States

In 1791, the new American Congress enacted a tax on distilled spirits to help pay off debts incurred during the Revolution. While popular enough to be easily passed in the House, there was one specific group that the tax did not sit well with: Western farmers. As much of their earnings came from using extra crops to make liquor, the farmers felt unfairly targeted by the legislation. Their unrest would prove to be the first major test of a constitution in its infancy.

Protests instantly broke out throughout Pennsylvania and those men compared the tax to a very recent memory: The Stamp Act of 1765. Given that it was this Act that ignited the flames of revolution and toppled British rule in America, this comparison was a frightening one for President Washington and his administration. It was imperative that these protestors be calmed down peacefully and without bloodshed.

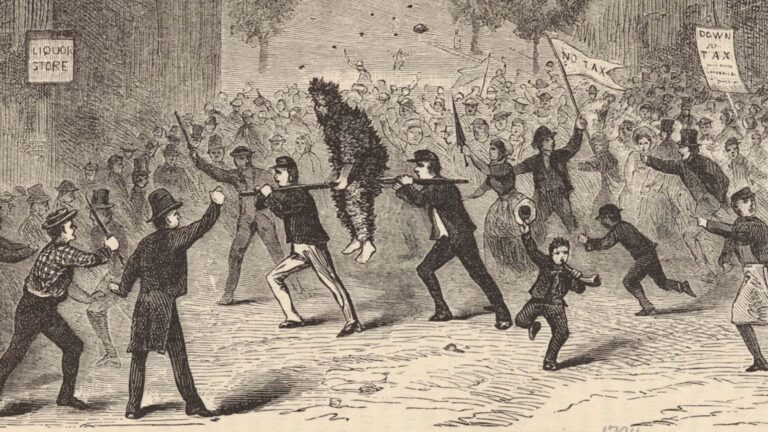

Opposition to the tax began with simple refusal to pay and harassment of tax collectors. One collector, Robert Johnson, was surrounded by a mob dressed as women. They pulled him off his horse, stripped him of his clothes, tarred and feathered him, and rode off on his horse. When a man was sent to apprehend members of the mob, that man was also tarred, feathered, and tied to a tree for five hours. Surprisingly, this was far from the worst of it.

Over the next few years, collectors and officials were harassed, assaulted, and threatened. The violence escalated to an armed confrontation in 1794 at the home of a wealthy landowner, John Neville, who was hosting a federal marshal at his estate, Bower Hill. Neville ordered the mob to disperse and when they refused, he fired a shot into the crowd and killed one of the men. Mayhem broke out. When the dust settled, the mob’s leader was dead, and Bower Hill had been burned to the ground.

Now a full-blown rebellion, several thousand men gathered in a Pennsylvanian field, threatening to lead an attack on Pittsburgh. This was a line that could not be crossed and President Washington was determined to not let things get that far. Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton implored the President to send in the troops, but he had one more idea: a peace envoy. They were sent to discuss a diplomatic end to the rebellion and were promptly turned away. There was only one thing left to do. President Washington gathered a militia across several states consisting of around 13,000 men and sent them marching to Pennsylvania. Only, the President had a surprise for the mob.

Leading the militia, in full military regalia, was not Washington the President, but Washington the General, riding in on his horse. Imagine the sight! One of the most fearsome and legendary soldiers of the day leading an army that dwarfs yours. It’s not surprising that the rebellion leaders immediately fled and the mob dispersed. The few that were arrested were eventually pardoned by President Washington. To this day, it remains the only time a sitting president has personally led an army.

“Famous whiskey insurrection in Pennsylvania” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1880.”

The Whiskey Rebellion, as it came to be called, was the first real test not only of the Washington administration, but the authority of the Constitution itself. Had the rebellion descended into all-out war, Americans would have felt that their new government too strongly resembled the tyrannical kingdom they fought so hard to free themselves from. Had Washington caved to their demands, the authority of the Constitution would be challenged for the rest of time. President Washington successfully established the legitimacy of his government while starkly distinguishing the country from the empire they left behind.

War and Peace

“A tax on whiskey is to discourage its consumption; a tax on foreign spirits encourages whiskey by removing its rival from competition.”

— Thomas Jefferson, 3rd President of the United States

Though the Whiskey Rebellion fizzled away, those affected by the excise tax had cause to rejoice in 1802, when President Jefferson repealed the 1791 tax on distilled spirits. President Washington had been adamantly non-partisan, but showed affection for Federalist causes. The next President, John Adams, was a proud Federalist. The election of anti-Federalist Thomas Jefferson in 1800 represented the first stark change in American economic policies.

President Jefferson did not think highly of internal taxes. As an anti-Federalist, he believed that Americans should be protected from the burden of government. Direct taxes, he argued, interfered with a citizen’s ability to economically thrive on their own. Critics immediately balked at the idea of rejecting the revenue stream of internal taxes. Jefferson wasn’t worried one bit. He felt that taxing imports from other nations in the form of tariffs would do more than make up for it. It had the added benefit of encouraging the purchase of American made goods, further stimulating the economy.

Throughout the course of the Jefferson presidency, all internal taxes were eliminated. This was the beginning of a decades-long era of little to no direct taxes on “regular” Americans except for when at war when more revenue was needed and importation plummeted. In fact, the 19th century’s taxes are quite formulaic in their ebb and flow in relation to peace and war. It would be Jefferson’s successor, James Madison, that would reinstate the whiskey tax to help America through the War of 1812. Several years later, peace set in, and the internal taxes went back out to sea for quite a while.

Then came the Civil War. Excise taxes came sailing back to land. Congress passed the Revenue Act of 1861, imposing taxes on a much wider range of items and, for the first time in American history, a tax on personal income. The income tax was designed to generate revenue from the wealthier Americans and leave the rest unaffected. Everybody who made less than $800 a year was exempt. By 1862, the Union realized this was no brief skirmish: more money was needed. Another act was passed, lowering the minimum taxable income to $600 and creating a new government office: Commissioner of Internal Revenue. It is this office that would become the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) we know today. Yet another act would come in 1864 to further boost revenue generation.

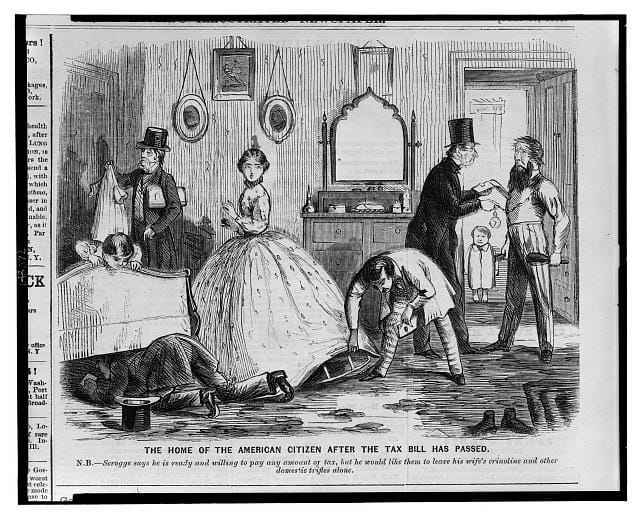

An 1862 cartoon depicting the “home of the American citizen after the tax bill has passed.” Government officials rifle through the family’s home, including under the wife’s crinoline.

With a bloodbath of a war, the horrible institution of slavery, and the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln behind us, it was time for our deeply fractured nation to attempt to heal. It was certainly easier said than done. The former Confederate states rejoined the Union only to find astronomical excise taxes on luxury items like alcohol and tobacco. This led to a boom in moonshining and, as if the country had not had enough, more bloodshed. Federal revenuers filtered into the mountains of the South to break up stills and were met with violent opposition from people protecting their land and their operation. These acts of violence bolstered the propaganda campaigns of Temperance advocates who painted moonshiners as savages, a stereotype that plagues moonshiners to this day.

Liquor and tobacco taxes provided a steady and hefty revenue stream unlike the country had ever seen before, reaching its peak at $310 million in 1866. This staggering record would not be challenged again until 1911. Satisfied with this number, Congress repealed the wartime income tax in 1872. The whispers and hymns of alcohol prohibition were growing louder and those advocates were paying attention. One thing was clear to them: the country would not survive without its liquor tax. That is, unless there was something in its place.