Liquor and Taxation: Part 2

Income Tax Incoming

“I am a tariff man standing on a tariff platform.”

William McKinley, 25th President of the United States

One of the fieriest economic issues at the turn of the 20th century was one that is sparsely discussed or understood today: the tariff. On top of the sin taxes, the tariff was an essential part of revenue generation for the government. In general, Republicans tended to support higher tariffs while the Democrats fought against them. While tariff proponents argued that costly imports would only encourage purchase of American goods, detractors claimed that it would be the American consumer who footed the bill as the price on goods skyrocketed. In the anti-tariff view, the tariffs were only good for American industrialists. It was such a contentious issue that it alone could swing elections.

In 1888, Benjamin Harrison, a Republican, had defeated incumbent Democratic President Grover Cleveland in that year’s election. Republicans took this as a sign that Americans were in full support of the Republican approach to tariffs. In 1890, Ohio Republican Congressman and future president, William McKinley introduced and successfully passed the Tariff Act of 1890 which would soon be known as the McKinley Tariff. The act included a rather dramatic increase on tariff rates. This increase proved so unpopular that President Harrison, who supported the tariff, lost the election of 1892 to none other than Grover Cleveland. It is the only time in American history that a former President has won the presidency back and therefore served non-consecutive terms.

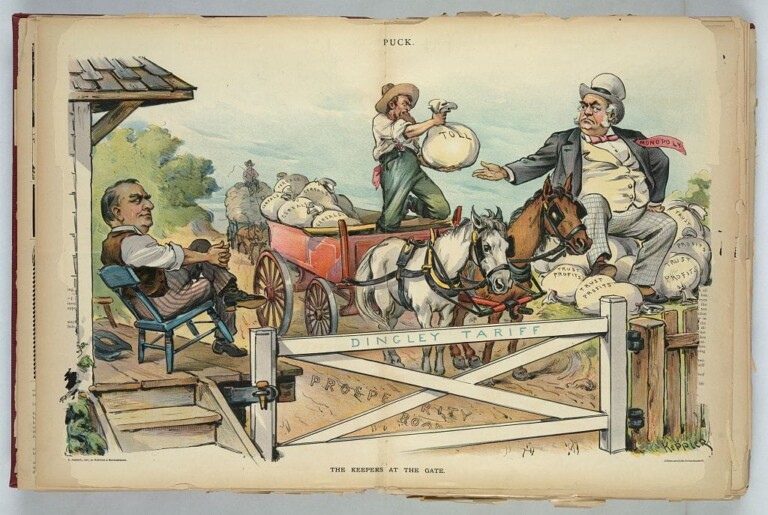

This 1897 cartoon criticizing a tariff act depicts the road to prosperity being blocked by a toll collector labeled “Monopoly” with President McKinley shown as the other gatekeeper.

With a new anti-tariff mandate from the people, Democrats got to work on a new tariff bill which would become the Wilson-Gorman Tariff Act which lowered the tariff rate and made up the lost revenue in a groundbreaking way: the first peacetime tax on personal income in the history of the nation. Democrats regarded the option as a “lesser of two evils” situation, greatly preferring an income tax over the tariffs. They passed the bill in 1894, but the battle was far from over.

In 1895, the Supreme Court struck down the income tax amendment of the Wilson-Gorman Tariff Act, arguing that the flat income tax imposed by it qualified as a “direct tax.” The Federal government is endowed with the authority to enact direct taxes so long as the populations of the states are taken into account. The opinion of the Court was largely based on the fact that this did not occur. One thing was clear: for a permanent income tax to be sustained, the Constitution itself would have to change, a seemingly insurmountable task.

The 16th Amendment to the United States Constitution

“The hardest thing in the world to understand is income taxes.”

— Albert Einstein, theoretical physicist

At the start of the 20th Century, many ambitious movements were all colliding at once. Tax proponents were not satisfied with their defeat in the Supreme Court a decade earlier. Suffragists were gaining momentum as they battled for enfranchisement. For more than fifty years, a massive crusade had been pushing for total prohibition of alcohol. One man used his immense platform to support all three.

William Jennings Bryan was a three-time Democratic nominee for president. Twice defeated by William McKinley in 1896 and 1900 and then once by Theodore Roosevelt in 1904, Bryan was nevertheless a pillar of the Democratic establishment with a vast amount of power and influence. By the time he became President Wilson’s Secretary of State in 1913, he had already publicly supported the income tax and Prohibition. This is not a strange combination, given how closely linked the two issues were.

The Anti-Saloon League, one of the chief groups behind Prohibition, was plagued in their efforts to enact national legislation for alcohol bans. While attacking liquor sales on a statewide level was easy and something that they were very good at it, their federal efforts were thwarted by what they called the “loss of revenue question.” They could not suggest banning alcohol nationally without being able to propose a viable way to replace the lost liquor taxes. They found a more than willing ally in the income tax lobby who were happy to support a Prohibition amendment in exchange for support of an income tax amendment. It was a match made in Progressive heaven.

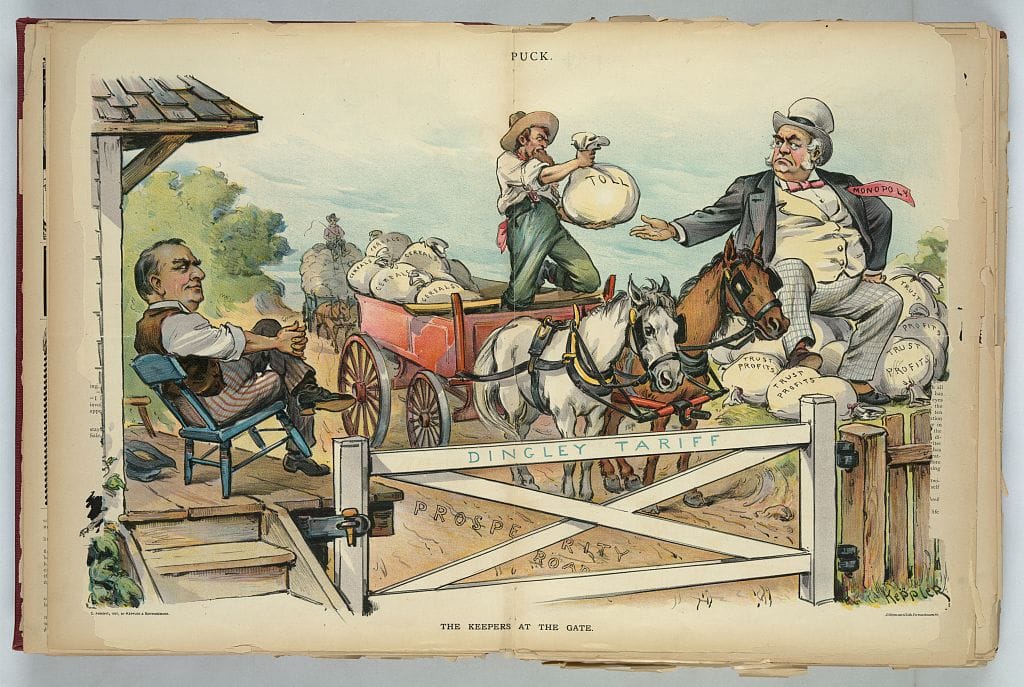

Wayne Wheeler as head of the Anti-Saloon League shrewdly calculated the alliance between Prohibitionists and supporters of the income tax.

Throughout the first decade of the century, the parties fought back and forth about taxes. While Republicans managed to repeal wartime taxes from the Spanish-American War, Democrats and progressive Republicans pushed for taxes on corporations and inheritance. Slowly, but surely, the scales began to tip in favor of an income tax. President Theodore Roosevelt declared that an income tax and inheritance tax should receive “the careful attention of our legislators.” He preferred an inheritance tax as he was still wary about the Supreme Court’s ruling from the prior decade. Still, he maintained that, if done right, an income tax would be “a desirable feature of Federal taxation.”

When President Roosevelt left office, he had personally chosen his successor: William Howard Taft. While picked by Roosevelt, President Taft approached the tax issue with more caution, temporarily soothing the fears of more conservative party members. Unfortunately, the feelings of the president began to matter less and less as a rift developed within the Republican party among conservatives and progressives. Attempts to deflate the push for income taxes, if successful at all, were only ever temporary.

In trying to bridge the gap between the two factions, President Taft promised to support a constitutional amendment authorizing federal income taxes. He was deeply worried about another brawl in the Supreme Court over income tax legislation. An amendment would settle the question about constitutionality once and for all. Taft did not believe the institution of the Court could survive another wounding in the public eye. Even better, the lengthy discussion and ratification process for a Constitutional amendment would greatly delay the tax itself. In fact, conservatives were sure the amendment would never make it out of ratification alive.

The 1912 election was a bitter one. The growing rift in the Republican party ruined their chances of reelecting their incumbent President Taft. His former mentor and predecessor, President Roosevelt, split from the Republicans to create the Bull Moose Party. This effectively divided the Republican vote and handed the election to Democratic New Jersey governor, Woodrow Wilson. On the bright side, the deliberation over the income tax amendment lasted just long enough for President Taft to leave office and avoid the fallout.

The Sixteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was fully ratified on February 3, 1913, taking effect later in the month. The conservative gamble to delay an income tax indefinitely had failed miserably. Soon after President Wilson took office, the tariff rates were lowered as a federal income tax was introduced, officially beginning the shift away from dependency on tariffs. This income tax collected a mere 1% of individual income over $3,000, but it wouldn’t stay that low for very long.

As with the wars of the 19th Century, the World War caused a precipitous drop in foreign imports which meant that the lost tariff revenue would have to be made up. As in the past, new excise taxes were introduced, but it soon became clear that a more productive income tax would be needed to usher the economy through the war. The personal income tax was doubled from 1% to 2% on income over $3,000 and a whole host of new corporate and excessive profit taxes were implemented. By 1917, the rate had remained at 2%, but now applied to income over $1,000. Nobody was more overwhelmed than the Bureau of Internal Revenue. From 1903 to 1915, they collected federal revenues of around $281 million per year. From 1915 to 1926, they were raking in over $2.78 billion each year. That wasn’t even close to the end of headaches for the Bureau. By the end of the war, annual tax increases were habit, but their next problem would be very different in nature.

Dried-Up Revenue

“Unquestionably our tax burden would not be so heavy nor the forms that it takes so objectionable if some reasonable proportion of the uncounted millions now paid to those whose business has been reared upon this stupendous blunder could be made available for the expenses of Government.”

— Franklin D. Roosevelt, 32nd President of the United States

The passing of the 16th Amendment had neatly paved the way for the passing of another amendment: the 18th Amendment. Without the aching burden of the “loss of revenue question” haunting their debates, the Anti-Saloon League moved swiftly to complete its mission of banning the sale of alcohol across the nation. On January 16th 1919, after only 11 months in ratification, the Eighteenth Amendment was fully ratified. The responsibility of enforcing Prohibition fell on the Bureau of Internal Revenue, adding a heap of work to their already overworked department.

In the years after the War, a seemingly never-ending series of tax cuts worked to undo the astronomical rates from the war. Some succeeded; some failed. The taxes could only be cut so much. After all, Prohibition cost an estimated $11 billion in lost revenue from the missing liquor tax. Much of the changes to tax policy in the 1920s proved to not mean much of anything as the Great Crash in 1929 and the advent of the Great Depression drastically mutated the American economy. However, even amid Prohibition enforcement and Depression relief, the income tax still managed to cement itself as a fixture of the American economy.

In 1932, a supporter of Prohibition repeal champions the idea that in “the good old days, good beer paid tax.”

On December 5th, 1933, with the ratification of the 21st Amendment, Prohibition came crashing to a halt on the national scale. The income tax had stepped in to replace the lost liquor taxes in the nearly 14 years of dry America. After Repeal, the income tax did not step aside to hand the reins back to excise taxes on liquor, but rather invited the liquor tax to join it at its side, working together to generate massive amounts of internal revenue.

Like many liquor-based laws, tax rates vary greatly state by state since so many states have such different approaches to regulating alcohol. These excise rates range from $2.00 a gallon in Missouri all the way up to a whopping $36.55 a gallon in Washington state. Wyoming and New Hampshire have no excise taxes on spirits, but, rather, generate their all tax revenue on hard liquor directly through state-controlled stores. Many states utilize government liquor stores, but only those two sell in a manner that eliminates excise taxes.

The marriage of liquor and taxes in the United States, though rocky at times, remains a devoted one. As long as Americans continue to distill and consume spirits, the government will, in part, depend on taxing those spirits to run the nation. If the Whiskey Rebellion, the Income Tax, and even National Prohibition couldn’t drive the liquor tax away, it seems as though it’s very much here to stay.